In 2021, our team went OUTBOUND to the remote Tuamotu Archipelago for the most exciting mission undertaken at Coral Gardeners: to develop a restoration project with the local community, who had observed a decline in the abundance and biodiversity of their lagoon. Proudly, this mission was made possible by a grant from the National Geographic Society, supporting two field expeditions on the atoll of Tikehau - our first major steps towards leveling up our restoration to a global scale.

FIRST THING FIRST: ASSESSING THE STATE OF THE REEF

The essential starting point for restoration to be successful is to assess the current state of the reef and identify the initial causes of degradation, which was the main goal of our first field expedition in Tikehau. In addition to utilizing the local knowledge of the islander community, we collected a series of data using the line intercept transect method, in which we extended 100-meter-long tapes along the seafloor to record various observations on the health of the reef ecosystem.

In total, we surveyed seven different sites, inside and outside the lagoon, to get a comprehensive overview of the state of Tikehau’s reef. For each site, we collected data on the environmental characteristics, the substrate composition and the abundance and biodiversity of the benthic life. These surveying efforts made for a whole lot of data to synthesize and analyze back at our headquarters in Mo’orea, to then set recommendations for the atoll’s coral restoration.

The results of our assessments found that the reef in Tikehau was in overall good shape, with some areas that could benefit from restoration. Our analysis allowed us to find potential donor sites of healthy corals that could help revive the damaged ones that we identified. For instance, we set our sights on the Coral Garden as a donor site, even though the substrate was composed mostly of non-living rock and rubble, the ratio of coral coverage was fairly good, and it showed no signs of bleaching or disease and almost no recently deceased corals.

In addition to the substrate study, the data on the fish and invert populations provided some interesting insights, finding evidence of a downward trend in the reef’s biodiversity. For example, among the inverts we surveyed, the giant clam was the most frequent species we encountered, yet most of them were very small (less than 10 cm), revealing a possible sign of local stressors, stopping these clams from growing and thriving – a potential link to unsustainable fishing practice. Since an array of life is needed to support a well-balanced ecosystem, a better understanding of the life on the reef was vital to develop our strategy.

EMPOWERING THE NEXT CORAL GARDENERS

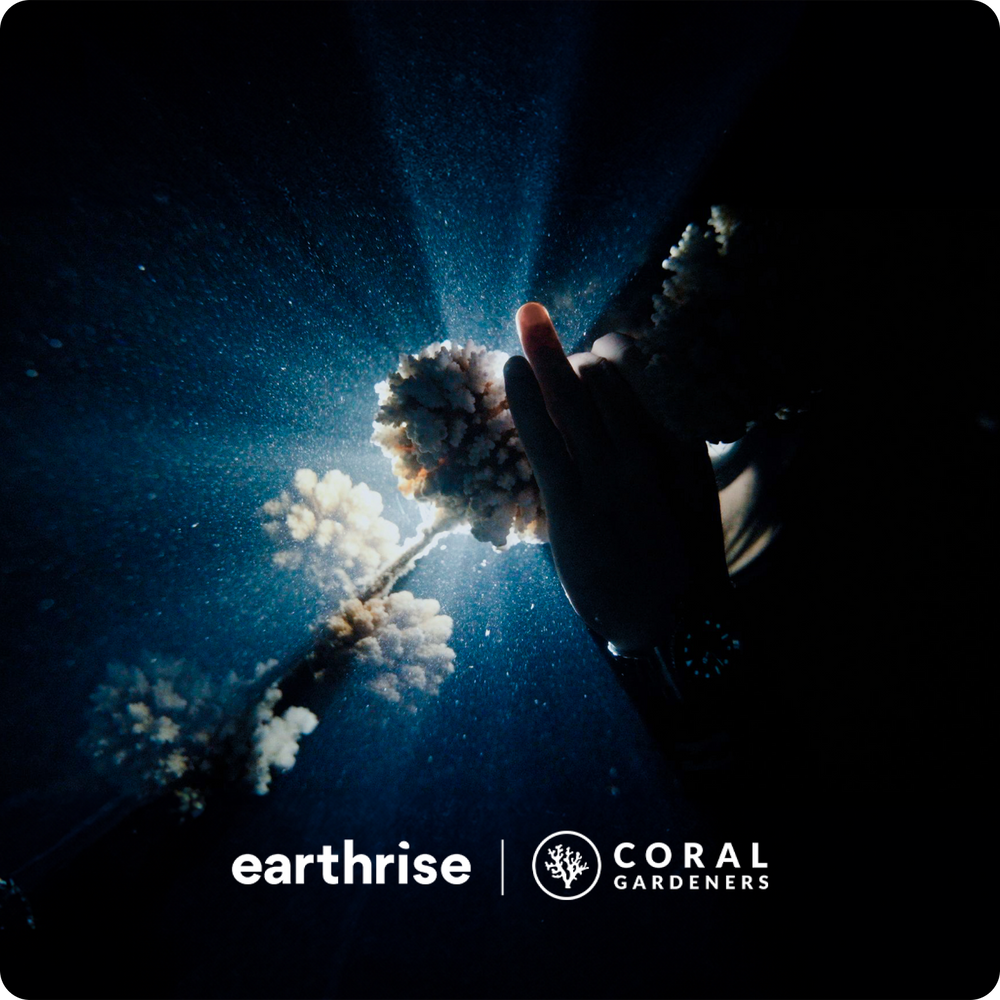

Going forward with this analysis, our plan focused on raising awareness and empowering the islanders to protect and preserve their reef. During our second expedition, we hosted different workshops to educate the community of local kids, women, men and fishermen on the importance of coral reefs and on how to mitigate stressors by teaching them the best practices to follow in the ocean. We also introduced them to coral gardening by setting up nurseries together, where corals are now blooming, to help preserve the reef, and thus, their livelihood.

The mission led to the opening of a new Coral Gardeners site in French Polynesia and will be used as a baseline strategy to adapt to the localized needs of other locations as we expand around the world. To learn more, make sure to watch our short film on YouTube.

This is just the beginning of many more expeditions to save the reef, one island at a time. If you want to join the family and help us scale up our efforts to plant 1 million coral around the world by 2025, you can donate on our website.